Current systematic and taxonomic research generally focuses on organizing and classifying taxa using a combination of characters, including chemical, molecular, morphological, ecological, physiological and biogeographical data. Researchers usually rank monophyletic lineages based on their distinct phylogenetic position, plus a combination of morphological and or other characters, and the level of ranking may thus follow that of their known sister clades. Taxon distinction is based on the recognition of monophyly, however, the rank of any taxon at any level is subjective and lacks universal criteria.

The first attempt at establishing a taxonomic system in the Fungi based on divergence time was a reconstruction of a taxonomic system for Agaricus (Zhao et al. Fungal Divers. 78:239-292, 2016). These authors produced a multigene phylogeny based on combined ITS, nrLSU, tef1-a, and rpb2 sequence data. Divergence times within the multigene phylogeny were calculated and used to standardize the ranking of taxa into subgenera and sections.

The following criteria were used to recognize taxa above species level: (i) they must be monophyletic and statistically well-supported in the molecular dating analyses; (ii) their respective stem ages should be roughly equivalent, and higher taxa stem ages must be older than lower level taxa stem ages; and (iii) they should be identifiable phenotypically, whenever possible. Based on those criteria some subgenera or sections were split or rejected, and new ones were discovered and named.

Recently, Dr. ZHAO Rui-Lin’s group provided a phylogenetic overview of Basidiomycota and related phyla in relation to ten years of DNA based phylogenetic studies since the AFTOL publications in 2007.

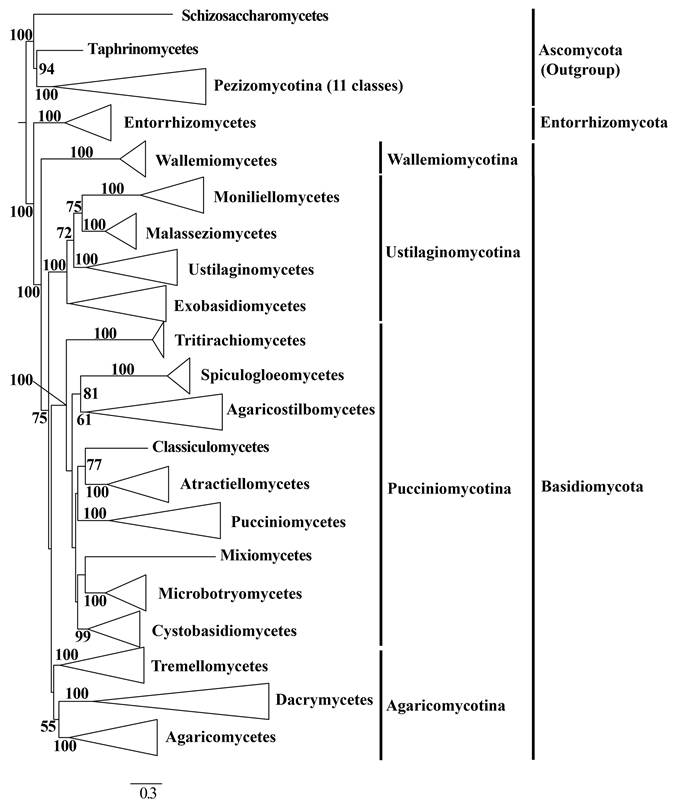

They selected 529 species to address phylogenetic relationships of higher-level taxa using a maximum likelihood framework and sequence data from six genes traditionally used in fungal molecular systematics (nrLSU, nrSSU, 5.8S, tef1-a, rpb1 and rpb2). These species represent 18 classes, 62 orders, 183 families, and 392 genera from the phyla Basidiomycota (including the newly recognized subphylum Wallemiomycotina) and Entorrhizomycota, and 13 species representing 13 classes of Ascomycota as outgroup taxa (Fig.1).

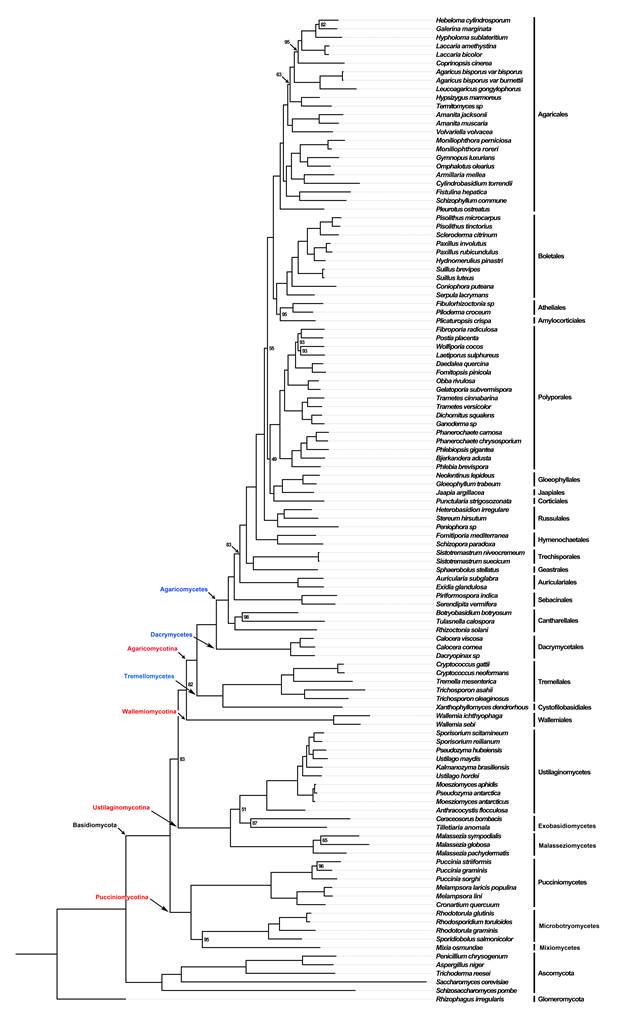

They also conducted a molecular dating analysis based on these six genes for 116 species representing 17 classes and 54 orders of Basidiomycota and Entorrhizomycota. Finally we performed a phyloproteomics analysis from 109 Basidiomycota species and 6 outgroup taxa using amino-acid sequences retrieved from 396 orthologous genes (Fig. 2). Recognition of higher taxa follows the criteria in Zhao et al (Fungal Divers 78:239–292, 2016).

The time-tree indicates that the mean of stem ages of Basidiomycota and Entorrhizomycota are ca. 530 Ma; subphyla of Basidiomycota are 406–490 Ma; most classes are 358–393 Ma for those of Agaricomycotina and 245–356 Ma for those of Pucciniomycotina and Ustilaginomycotina; most orders of those subphyla split 120–290 Ma (Fig. 3). Monophyly of most higherlevel taxa of Basidiomycota are generally supported.

However, the younger divergence times of Leucosporidiales (Microbotryomycetes) indicate that its order status is not supported, thus we propose combining it under Microbotryales.

On the other hand, the families Buckleyzymaceae and Sakaguchiaceae (Cystobasidiomycetes) are raised to Buckleyzymales and Sakaguchiales due to their older divergence times. Cystofilobasidiales (Tremellomycetes) has an older divergence time and should be amended to a higher rank. We however, do not introduce it as new class here for Cystofilobasidiales, as DNA sequences from these taxa are not from their respective types and thus await further studies. Divergence times for Exobasidiomycetes, Cantharellales, Gomphales and Hysterangiales were obtained based on limited species sequences in molecular dating study. More comprehensive phylogenetic studies on those four taxa are needed in the future because our ML analysis based on wider sampling, shows they are not monophyletic groups.

In general, the six-gene phylogenies are in agreement with the phyloproteomics tree except for the placements of Wallemiomycotina, orders Amylocorticiales, Auriculariales, Cantharellales, Geastrales, Sebacinales and Trechisporales from Agaricomycetes. These conflicting placements in the six-gene phylogeny vs the phyloproteomics tree are discussed. This leads to future perspectives for assessing gene orthology and problems in deciphering taxon ranks using divergence times (Zhao et al. Fungal Divers 84:43-74,2017).

Fig. 1. A summary concatenated tree showing the relationships among classes from the phylogenetic analysis of Basidiomycota and allied phyla generated from maximum likelihood analysis of nrLSU, nrSSU, 5.8S, tef1-α, rpb1 and rpb2 sequence data, rooted with 13 species from Ascomycota. Bootstrap support (BS) values > 50 % are given at the internodes. (Image by Dr. ZHAO’s group)

Fig. 2. Phyloproteomic tree of 109 Basidiomycete and 6 outgroup species, based on 396 protein alignments and a total of 82,536 sites. Statistical support values are based on maximum likelihood, and are shown only for nodes with lower than 100% support. (Image by Dr. ZHAO’s group)

Fig. 3. Maximium Clade Credibility tree of Basidiomycota and allied phyla based on nrLSU, nrSSU, 5.8S, tef1-α, rpb1 and rpb2 sequence data with the outgroup Entorrhizomycota. Posterior probabilities which are equal and above 80% are annotated at the internodes. The 95 % highest posterior density of divergence time estimates are marked by horizontal bars. The coloured dots

refer to the positions of the mean stem age of phyla, subphyls, classes; and orders respectively. (Image by Dr. ZHAO’s group)

refer to the positions of the mean stem age of phyla, subphyls, classes; and orders respectively. (Image by Dr. ZHAO’s group)

Contact:

ZHAO Rui-Lin

State Key Laboratory of Mycology, IMCAS

E-mail: zhaorl@im.ac.cn